-

davide balliano

-He works across many mediums, makes work and research constantly and needs to have a lot of order in his life.

New York-based Italian artist Davide Balliano had a conversation with me about his artistic trajectory, his work, rock climbing, his influences, his love of intervention and his first show in Paris at the Galerie Michel Rein.

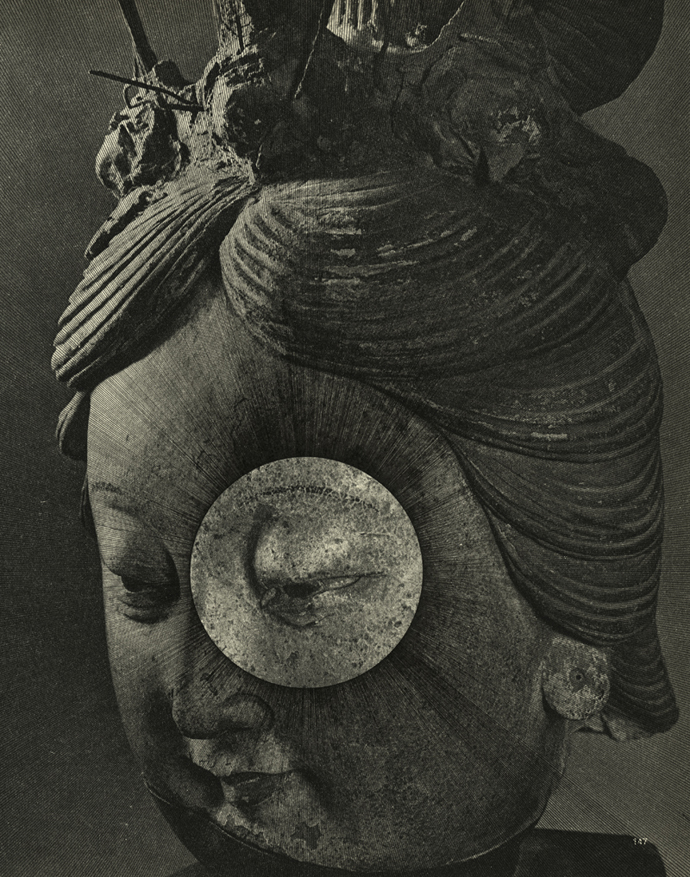

Davide Balliano UNTITLED_Woman V Ink on book page 21x26,8 Cm 2013 Courtesy: Michel Rein Gallery, Paris

Lynsey Peisinger: Tell me a bit about your life and your path as an artist.

Davide Balliano: I was born and grew up in Torino, in the northwest of Italy. I was there until I was 18 and then I started in high school studying advertising and graphic design. It was a very peculiar school, a very specific school, which had a lot of elements that are still useful for me now. Especially the graphic design elements, the study of the image, the history of the image, art history. All of that is still informing my work today.

After that, I moved to Milan where I studied photography at Bauer, which is a fabulous school of photography. It is probably the last public school of photography that is left in Italy. What I liked of the school was the approach that they had, that I think they still have now, where rather than teaching “photography as a job”, they tried to raise us as artists working in the medium of photography. They train you as an artist who used the tool of photography. Then what you do with that tool is your choice.

Two years after school, I went to Fabrica, which is a large artist residence in Treviso, in the north east of Italy, a half hour from Venice. It is a beautiful place. A huge building built by Tadao Ando and there are usually approximately 40 artists in residence. It was very commercial-based. There is not much interest in pure artistic research. It’s more applied art. It was a very good experience–they pay you be there, they give you studio, they pay for all of your materials, they give you an apartment. You don’t have to worry about anything. But, even if it was great, it sort of crushed my relationship with photography. Fabrica had a very strong way of shaping the people that were there, so they were not making it a mystery that they couldn’t care less about the kind of photography that I was doing! I was very young, I was 21.

After Fabrica, I stayed one more year in Milano, then I got badly bored of staying in Italy. So I moved to NY in 2006. And it is in the early time in NY that I started to do other stuff. I felt that this move to NY was sort of giving me a clean cut from everything that I did until then. I sort of put photography a bit on the side and I started to draw and to intervene, but still on photographic images. I assume that because of my background in photography, I always have a difficult time starting anything from a blank background, you know from a white slate. For me, it has always been terrifying!

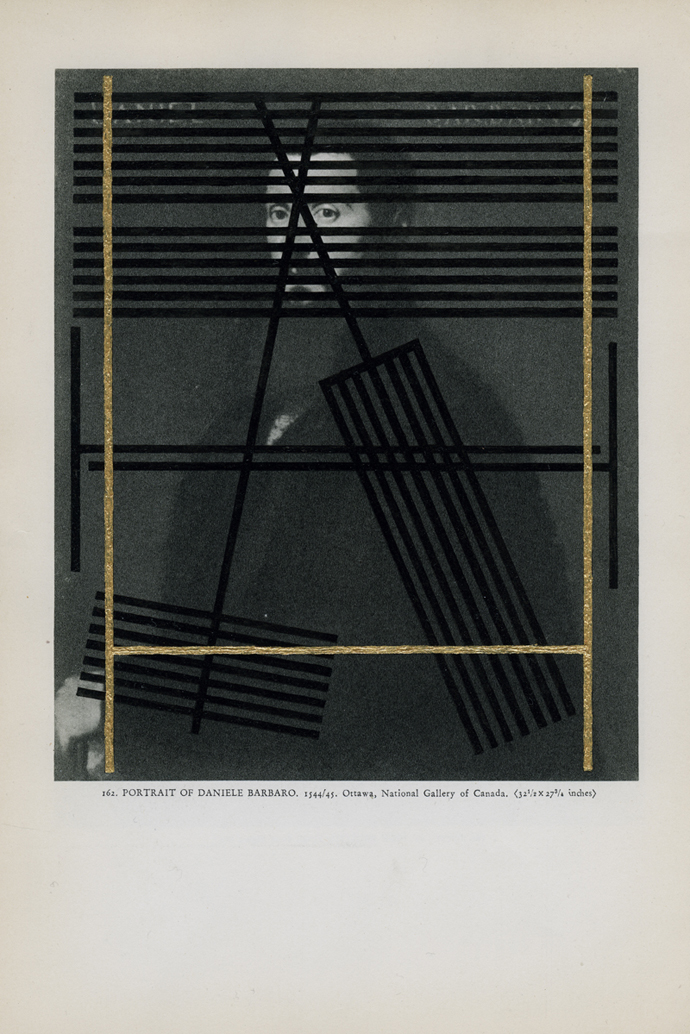

Davide Balliano UNTITLED_Barbaro Watercolor and acrylic on book page 18x25 Cm 2012 Courtesy: Galerie Rolando Anselmi, Berlin

LP: How did you start to move into the mediums you are working with now?

DB: So I started to print out images, mainly from the internet at that time. I still collect a lot images just for my inspiration. And I started to draw freehand on them, mainly abstract geometrical mess! Abstract scribbles, nothing with a precise meaning. Pretty soon, it sort of got clear that the issues that I had with photography were still there–even if I am intervening on top, I still had to take care very much of the meaning of the background image.

There are some images that you can just use for their mood, but there are other images that have a precise meaning that carries responsibilities. I think that this is something that you can use but you need to be conscious about it.

I always hate any kind of work in any kind of medium that just takes strong images and slams them there without standing by it. I always find that it’s a very cheap shortcut. It is something that I always hate.

So, then I started to draw on art history images because I felt that they left me more freedom somehow because there is already a big gap. You are more free to relate with the feeling of the image rather than with historical facts. The facts are there and I agree that I should deal with that, but there is a distance so there is a larger filter. So if I make a drawing on top of a portrait of a king, I should probably do research about who it is etc, but I don’t. And most people wouldn’t say “why did you make a drawing on this king and not on another one?”.

If you do the same kind of thing in photography, it is difficult because photography is such a young medium that almost any photographic image is in a historical context. So from there, the intervention grew more and more precise and became more and more essential. So if you take a drawing of four or five years ago, which was abstract and geometrical, but still messy and not so calculated, they sort of condensed somehow and at some point, it felt a need to take this intervention that I was doing on paper and put it on other mediums.

I burned that town just to see your eyes shine Wood and glass 137x48x48 Cm 2012 Courtesy: Galerie Rolando Anselmi, Berlin Photo: Nikki Brendson

LP: Tell me a bit about the medium of performance.

DB: Performance, which I do although rarely, is a different thing although I feel that it is strongly connected to….photography. It is interesting, I feel that performance is strongly connected to photography because I still feel it as the production of an image. An image that is locked by a location and by a time. I am very fascinated by the potential of making a legend with performance, not necessarily mine. Sometimes you see performances that are unrepeatable–the original work is born in one place at a specific time and if you were there, there is nothing that can repeat that moment. And it gives you something that is so unique, it sort of makes you part of the history of the work, much more than in other mediums.

Most of the time in other mediums, the work is done by an artist and then is shown. And the artwork has a life and it will be the same life for the next many many years. But a performance is in a place and in a moment and if you were there, you had the privilege of being part of it and then nothing will take that away. I find it fascinating. And I relate to it as the creation of an image, practically speaking.

LP: It sounds like performance gives you an opportunity to experience being an artist in a different way.

DB: Exactly. And also seeing what it means for other artists. It has been great because I am completely incapable of doing it in any other medium. I am sort of a control freak for anything else that I do. I know that in performance, I very much enjoy opening up to collaboration and seeing what it brings.

LP: At which point in your life did you realize that you wanted to be making art? Was it from childhood? Did you go to that graphic design school because you knew that already about yourself?

DB: Well, I will say that it depends. I always, since when I was a kid, felt an extreme need for creative expression. So I always had no doubt that I would be doing something creative in life. But, the decision to make exclusively art research sort of developed over the years. It felt like everything else just dropped and it stayed there. For all of my school time, I had the idea that it was impossible to only do that.

I always thought “I need to do something else on the side”. For example, I thought I could do graphic design while doing other work. Also with photography, but photography was even closer to making pure artwork. But it was an idealistic idea that I could be an artist but also make commercial stuff. I needed to take a decision between the two things. And I think that especially when you are young, people want one or the other.

Another thing that I understood–I sound like an old grandfather saying “when I was young…etc”! — When I was in high school I was doing a lot of rock climbing and at a certain point I had a trainer and was training five days a week. I loved it, but I liked to go out and go to concerts too. I had my social life which was very important to me. Everyone else there was like a monk about it. Just training, training, training. They ate only certain food, they were constantly on a diet. Complete dedication. I understood that I couldn’t at all put in that type of dedication and I couldn’t compete with people that were that dedicated to it. And later, I felt the same way with photography.

If you are trying to do something good, you should consider that most likely there is somebody else that is trying to do it and he is going to be very good at it and he is going to put all his energy into it, he is going to make tons of sacrifices and he is going to go through hell to achieve it. So if you are not up for that, you are in for a competition that will never bring you anywhere. So photography for me was sort of like that.

I was in Milano therefore everything was about fashion photography. I mean, fashion photography was fun! I would go to a set, with models and people and music. It’s all fun. But if you are trying to do it, you are in competition with 500 kids obsessed with their freaking portfolios who are putting their money into making fashion photography. I’m like “hell no”! I have to be paid to make fashion photography, not the other way around. People would tell me that I had to put together a fashion photography portfolio and then when people look at you because of that, you bring in your art research. But for me, I knew I would not have the energy to do that because I was already putting all my energy into my research. And I sort of became clear that it wouldn’t work. I had to push on thing or the other.

So I decided only to concentrate on art. I assisted for many years. I wanted to learn from an artist. I wanted to learn about art-making and also the practical side of it.

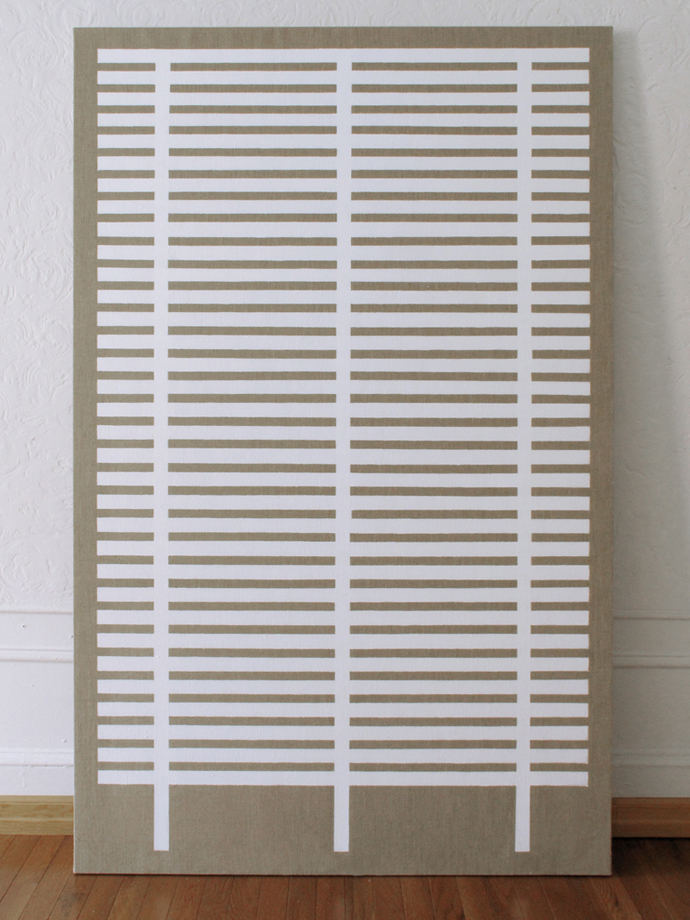

Davide Balliano UNTITLED_Grid27 Acrylic on linen 120x180 Cm 2012

LP: When you came to NY, you assisted Marina Abramovic for four years. How did that experience influence your work and how did it prepare you for your own path as an artist?

DB: For me, Marina was like my own private university. She taught me everything that I know about surviving as an artist.

Independently of the love that I have of her work–I approached her because I always had an extreme fascination with her work– the privilege that I had when working with her was that I was in contact with the private side of her. And what I gained from the private relationship is to see how she is completely dedicated to her work. Marina is all work. And there is an insane amount of energy and dedication that she puts into it. Her work is her life, there is no separation, there is no in between.

The personal investment that she makes in her work, I assume gives her this concentration that comes out so clearly in the work. And, other than that, she is such a big artists that if you work with her for four years, afterwards you can truly do anything. I came out of that experience being practically scared of nothing.

Marina works at such a level of intensity that there is really nothing that you can’t do after that. It is like boot camp. You are so used to working under pressure –good pressure, but pressure–daily. Everyday was the same amount of concentration and speed and pressure. The responsibilities are always big. There is never a day that you go and pick up flowers! Every day is something big, something important, something that you can’t mess up. When you do that every day for four years, you come out and truly its like those American movies about Marines. You can really do anything!

LP: You seem to have an approach to your work that is extremely organized and structured. It seems to me that are an artist who approaches your work like one might approach any business in terms of how you structure and use your time and also how you interact with and deal with people. I wonder if working with Marina influenced that or if you were always someone who could self-motivate and give order to your life.

DB: Definitely working with Marina, and my other assistant jobs, gave me that structure. Marina is naturally 80 percent of it, but everything contributed. Assisting fashion photographers meant being efficient and fast. There are a lot of responsibilities and you have to work under pressure, so you get used to needing to maintain focus. Keeping your concentration on the work itself under all the pressure seems to me to be the secret that all of these big guys shared.

There are tons of different kinds of artists and I know fabulous artists that work in complete chaos and it’s fine for them. Their art can come out of that. They can do nothing for weeks and then disappear and work day and night for a month and then come out like drained zombies, but the resulting work is marvelous.

But that’s not for me. The less I do, the more in pain I feel.

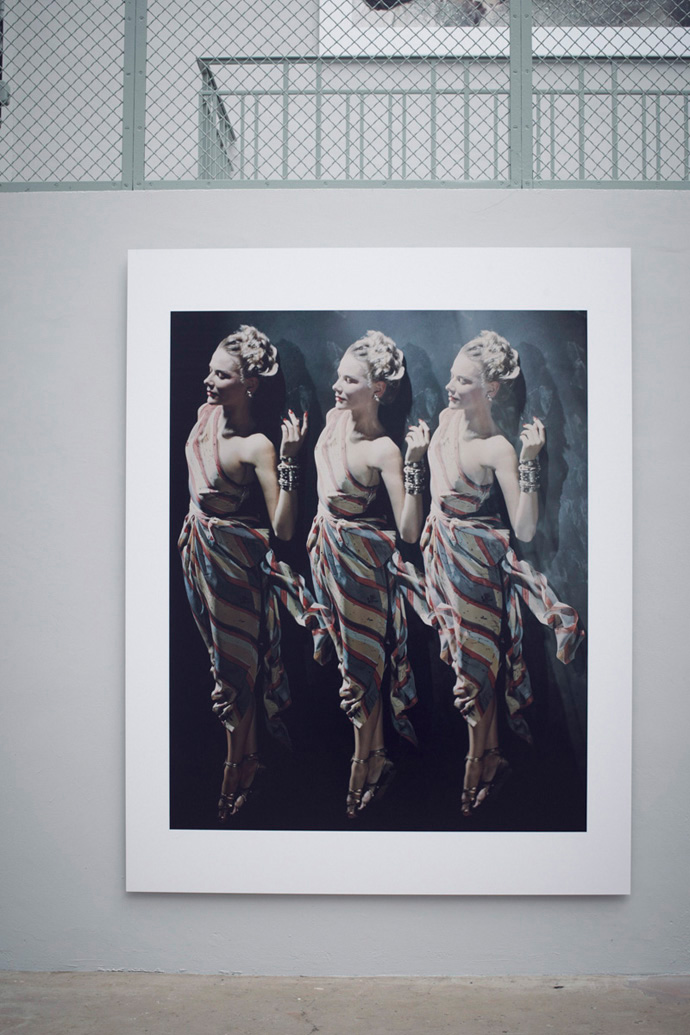

Davide Balliano PICATRIX, installation view Courtesy: Michel Rein Gallery, Paris

LP: Tell me about that show in Paris.

DB: The show in Paris started with an invitation from Eugenio Viola, a wonderful curator that I worked with last January. He invited me to have this little show and he set the theme of the show. He asked me to work with the concepts of alchemy and symbolism and sort of esoteric feelings, which is something that is present in my work even if I don’t always relate to those things in my life.

There are four works on paper, two paintings on board and one sculpture. We see a combination of different mediums and the dialogue that they have with each other, which is very important for me. I never make a show that deals with only one medium because it feels like a small part of what I do. I feel like I can’t say what I want to say with one medium, I have to put them together.

In the past Alchemy was called “the great work” and I love it. I like the utopic idea that through my work, and the elements given to me, I can control these elements and have a higher understanding of who I am and a higher consciousness.

Eugenio asked me to consider these things and to put together a little show that gives my view on these topics, so I did.

LP: What is the last thing that stimulated you?

DB: The film The Turin Horse by Bela Tarr. It is really stuck in my mind and I keep on thinking about it. It was very very strong for me. And not because I am from Turin! Its strict and minimal and powerful and its a complete tragedy. There is no space for hope, no space for light, like a classic tragedy. Everything is rotting and closing in on you. Sometimes I feel that tragedy might be more inspiring than happy thoughts. Happy thoughts are private while tragedy can be shared and if you recognize the suffering in someone else, it can make you feel less alone in your own troubles. That is probably why all of the work that I strongly admire has a heavy portion of tragedy and weight.

PICATRIX at Galerie Michel Rein, curated by Eugenio Viola

http://michelrein.com/

http://www.davideballiano.com/00 -

Life and Death of Marina Abramovic – vii

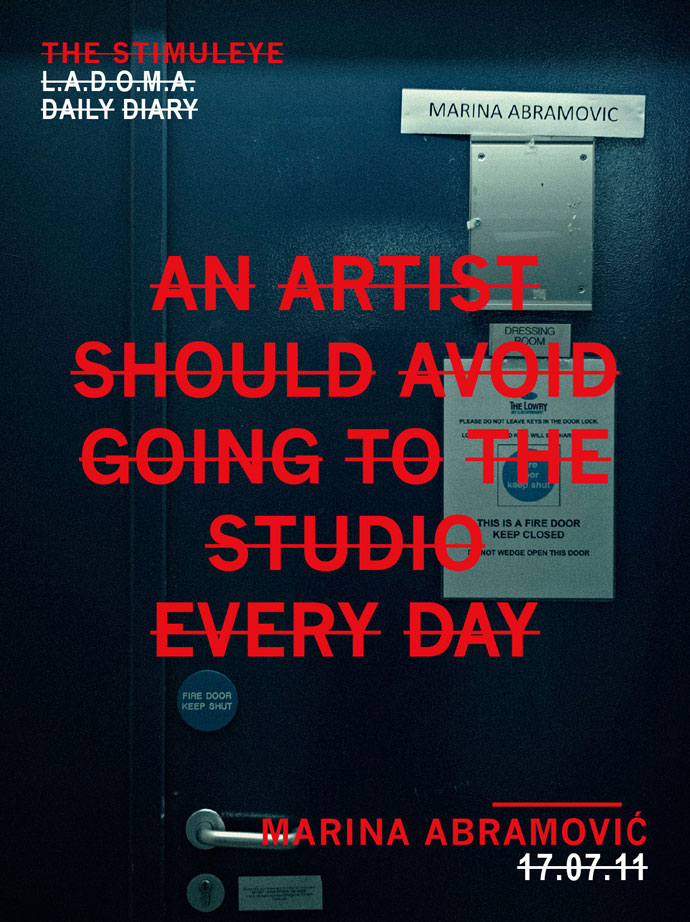

-“An artist should avoid going to the studio every day”

STUDIO

Last night was the last performance in Manchester.Everyone in the cast and crew will soon be returning to their “normal” life, wherever it may be around the globe, to their city, their apartment, their studio.

Over the last week, seven exhausting nights, the play is ending.

It has been seen by Viktor & Rolf, Riccardo Tisci, the director of the MoMA and many others.But fear not, it will return, soon, somewhere else around the globe.

-

life and death of marina abramovic – vi

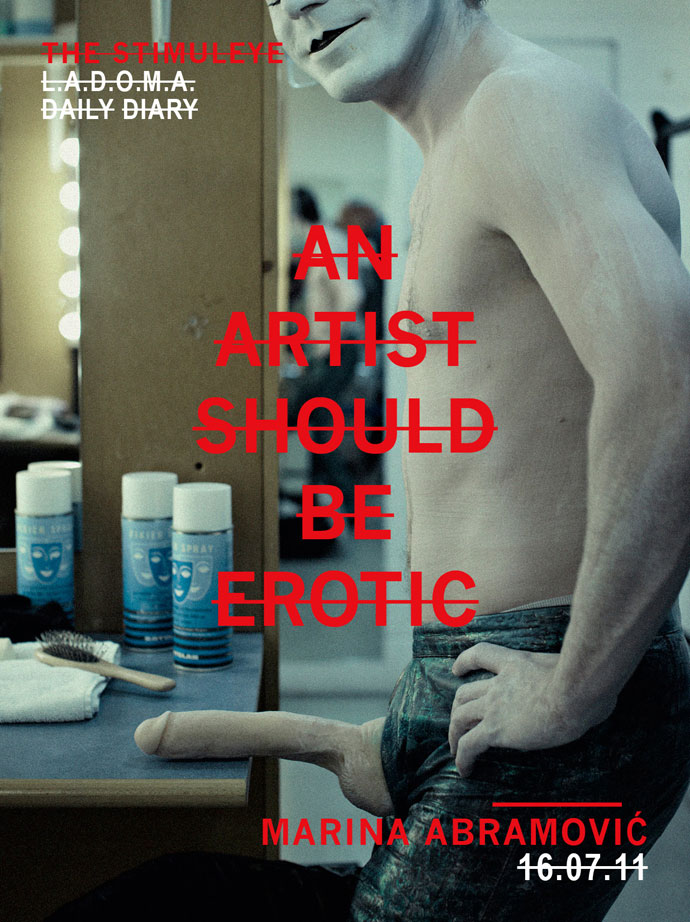

-Marina's 6th commandment. Photo by René Habermacher.

DICK

This is not a dick.

It’s a strap-on.

It’s strapped on a man, Andy.In the play, Andy masturbates while wearing a mask of Marina, as she flirts with him.

Tonight is the last night to see this, as it is the last night the play is performed in Manchester.

-

LIFE AND DEATH OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC – V

-“An artist should stay for long periods of time at exploding volcanoes”

Marina's fifth commandment. Photo by René Habermacher.

THE WIG

This is the wig of Willem Dafoe when it’s not on Willem Dafoe.

It’s in the make up room.In the play, Willem appears as a demonic, cartoonish narrator, meticulously going through Marina’s life chronologically, year after year.

-

LIFE AND DEATH OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC – IV

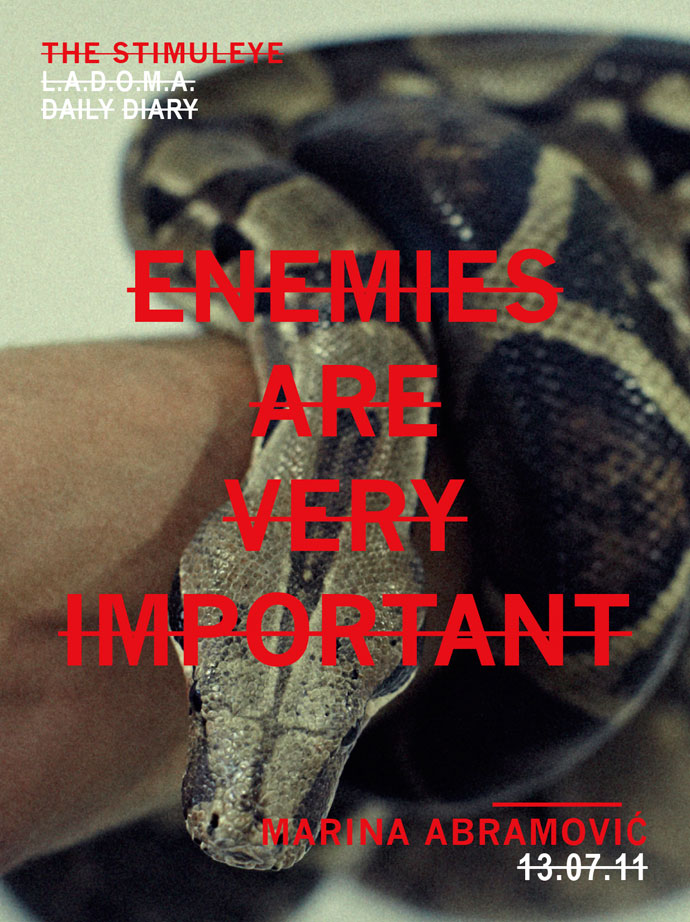

-“Enemies are very important”

Marina's fourth commandment. Photo by René Habermacher.

THE SNAKE

After an energetic premiere, the play keeps running until the 16th.One of the cast we havent yet introduced is Daisy, the boa constrictor.

Like bruno’s predecessor was stiffy, Daisy replaced the rolled-up blanket used for rehearsals.She naps in her well temperated box towards the minutes of spotlight.

It was difficult to find a hotel for her, says David the “snake-man”, so many houses had refused them shelter…Daisy and David. Photo by René Habermacher.

-

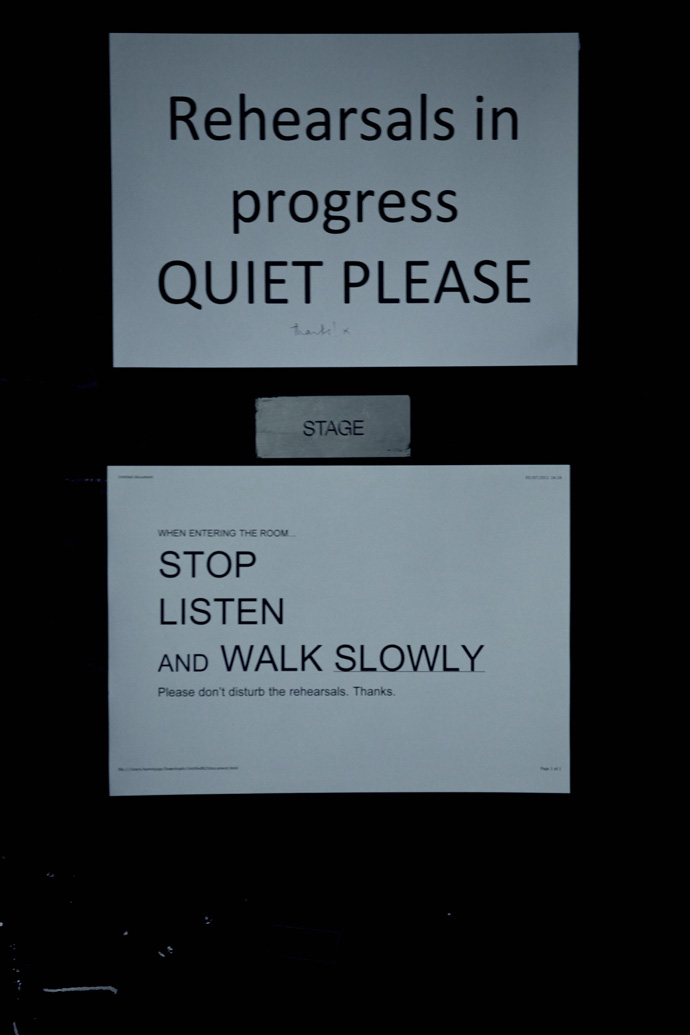

LIFE AND DEATH OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC – LAST REHEARSAL

-Marina, Willem, Bob, Carlos and the Serbian girls.

Only a few more hours left to marinate, before the feast.The stage doors. The note is to be taken very serious. Photography by René Habermacher.

Today Marina had her shaman coming from Santa Fe, New Mexico, in order to clear any bad spirits in the theater.

Magick is in the air, the mood has eased the morning following the preview.

Some eruptions excluded.Willem Dafoe noting remarks on his text. Photography by René Habermacher.

Preparations in the Make up rooms. Photography by René Habermacher.

After all, the puzzle of endless rehearsed scenes makes sense now, its emotional power in effect to captivate both spectators and cast.

As the premiere nears, the ticket office and press department whirl faster.

During breaks, we hear big names to will attend.

They have to be seated the right way. Tickets are limited and getting sparse.Carlos Soto. Photography by René Habermacher

Marina Abramović and Antony Hegarty. Photography by René Habermacher.

The Serbian girls, that form the chorus with peasant songs, cook and cater everyone with traditional baked beans.

The longer they marinate, the better they are supposed to get. Though the longer you leave the beans to marinate, the higher the risk of having your portion snapped away – perhaps we should put name tags on the glasses in the backstage fridge?

Anyway, it’s all about MARINAting. The effect is, it melts on the tongue….

Marina riding on her wooden horse Bruno. Bruno is a darling, but not too comfortable... Photography by René Habermacher.

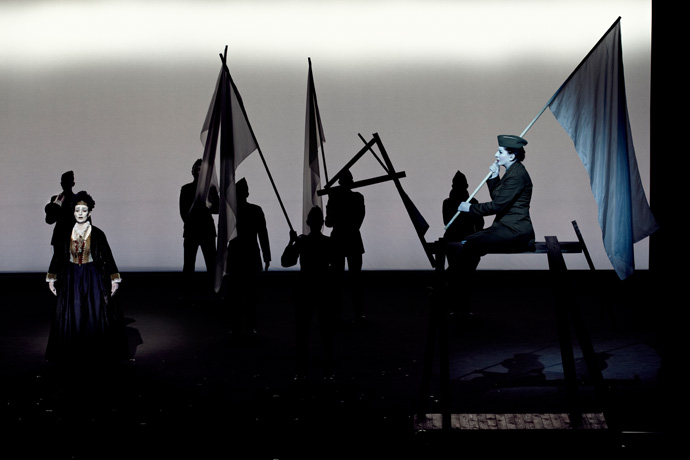

Svetlana sings the chorus while the soldiers shout parts of Marinas artist's manifesto. Photography by René Habermacher.

Life And Death Of Marina Abramovic

at Manchester International Festival

July 9 – 16, 2011. -

LIFE AND DEATH OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC – III

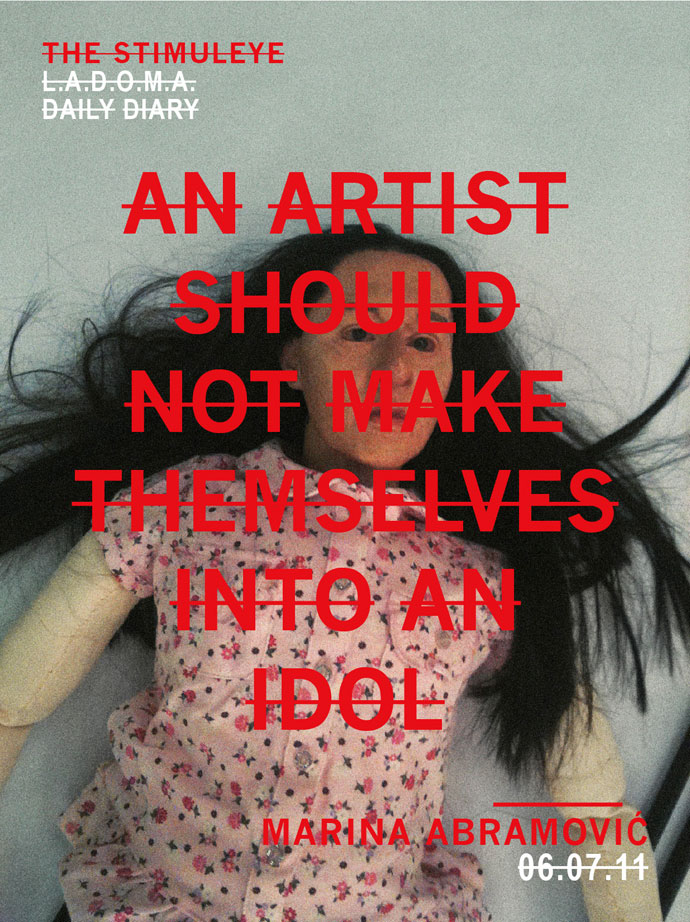

-“An artist should not make themselves into an idol”

Marina's commandment III. Photo by Lynsey Peisinger.

MINI-MARINA

Mini-Marina is a doll that wears Marina’s own, real hair.It just flew in from New York City.

The costume department is working on dressing Mini-Marina for the premiere…

Life And Death Of Marina Abramovic

at Manchester International Festival

July 9 – 16, 2011. -

LIFE AND DEATH OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC – II

-“An artist has to be aware of his own mortality”

Marina's Commandment II. Photo by Lynsey Peisinger.

MASK

Its raining in Manchester. Although sometimes not.The first preview went on stage under the roof of that building where his architect threw himself from his landmark tower to death.

Marina thinks there must be some energy left from this.At Marina’s funeral, who do you expect to see in the coffin? Marina, obviously. Since we have three people in both of Marina’s funeral scenes, they decided to make everyone wear “Marina masks” so that everyone would look like her.

We call them “Marina Death Masks”. They looked much more morbid before they put makeup on them…

-

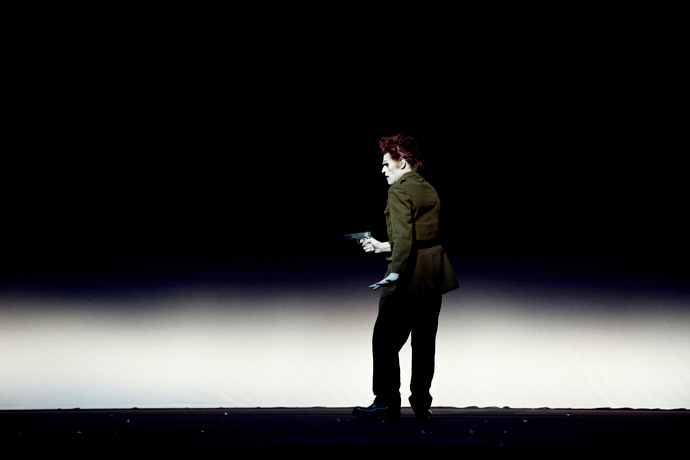

LIFE AND DEATH OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC : GUNPLAY

-Four more days to go until the premiere. The rehearsals proceed until late at night with great concentration. After four weeks of work, the cast, creative team and crew are almost ready for the first preview tonight. Bob Wilson, Marina Abramovic, Willem Dafoe and Antony Hegarty. An ensemble this beautiful doesn’t happen very often, perhaps just once in a lifetime.

The premiere is just hours away. Bob is orchestrating his cast and crew and the multi chromatic illumination of the play. Antony continues to conduct the music, snapping the tempo for the band while singing on stage. Willem recites his text in an endless mantra, a flood of whispers. His face and body moving through their various expressions. There is tension under the roof of the Lyric Theatre at the Lowry in Manchester. There have been troubles and tears and there have been shiny moments of camaraderie and playfulness, all in an effort to tell you a story. The story of Marina’s life. It is a story that will carve out a space for her in your heart forever…

Now, we go into our last rehearsal before the preview. The vultures are flying, Marina is slipping into her red, feathered dress and Bob….well, Bob is setting light cues.

Robert Wilson instructs Wilem Dafoe in Gunplays. Photo by René Habermacher

Robert Wilson instructs Wilem Dafoe in Gunplays. Photo by René Habermacher

How Willem plays the gun. Photography by René Habermacher

How Willem plays the gun. Photography by René Habermacher

And finally on stage: "Bruno" as Marina calls him is the new Horse that replaces "Stiffy".

So here Bruno, Willem and Marina. Photography by René Habermacher

And finally on stage: "Bruno" as Marina calls him is the new Horse that replaces "Stiffy".

So here Bruno, Willem and Marina. Photography by René Habermacher -

LIFE AND DEATH OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC – I

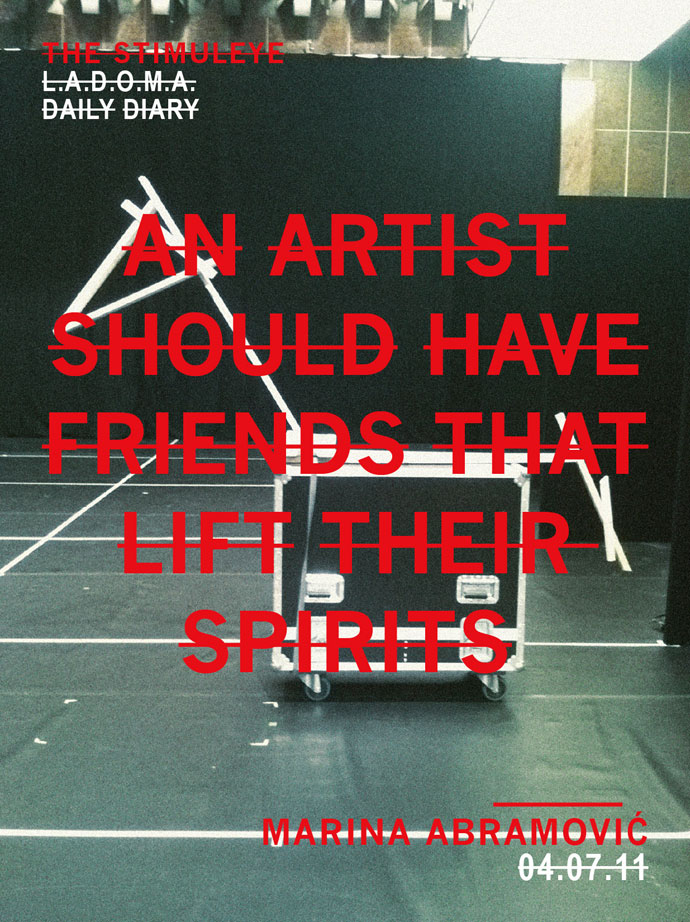

-“An artist should have friends that lift their spirits”

Marina's commandment I . Picture by Lynsey Peisinger.

STIFFY

The first three weeks of rehearsals were held in a rehearsal space where we used temporary props and stand-in animals.Stiffy (aptly named by Willem Dafoe) was Marina’s stand in horse. We miss Stiffy now that we are at the theatre and the “real” horse has arrived.

He had a very wide body and Marina had to walk like a cowboy after sitting on him for too long.

But he was good to Marina for those weeks.Life And Death Of Marina Abramovic

at Manchester International Festival

July 9 – 16, 2011. -

ANNOUNCING THE LIFE AND DEATH OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC – MIF DAILY DIARY

-The Stimuleye is proud to be announce the upcoming series “The Life and Death of Marina Abramovitch” – MIF Daily Diary.

Under the direction of Robert Wilson, and with the participation of Antony Hegarty, Willem Dafoe and, of course, Marina Abramovic, this exceptional performance will run July 9 to 16, 2011 at Manchester International Festival, but you’ll be able to follow all the preparations right here, on the The Stimuleye.

Stay tuned…

Willem Dafoe, Marina Abramovic, Antony Hegarty and Robert Wilson. Photo by Antony Crook.

Life And Death Of Marina Abramovic

at Manchester International Festival

July 9 – 16, 2011. -

ERWIN BLUMENFELD: through the eyes of his son Henry.

-On the second day of the fashion and photography festival in Hyeres, I watched Henry Blumenfeld, elementary particle physicist and son of Erwin Blumenfeld, inconspicuously walking through the exhibit of his father’s work at the Villa Noailles. He was wearing a tan suit, sneakers and a baseball cap that was slightly crooked on his head. Before long, the spacious, bright room where the artist’s photographs and videos were being exhibited became empty and quiet. Only the slight hum of voices around the villa could be heard through the walls. Here, surrounded by a collection of stunning and rare examples of his father’s work — large-scale, restored prints — Henry sat down with us for an intimate conversation: Erwin Blumenfeld the artist, the father, the mentor and the man of perseverance.

by Lynsey Peisinger, Photography René Habermacher

Son Henry Blumenfeld in front of his fathers DOE EYE with Jean Patchett for Vogue US 1950

Son Henry Blumenfeld in front of his fathers DOE EYE with Jean Patchett for Vogue US 1950LYNSEY PEISINGER: Where were you born?

HENRY BLUMENFELD: I was born in 1925 in Zandfoort near Amsterdam. My father had been an ambulance driver during the first World War. During the war, he had met my mother who was Dutch, Lena Citroen, who was a cousin of Pal Citroen, a German/Dutch artist. He grew up in Berlin with my father and they went to school together and they were very close friends. Through Pal, he met my mother and they corresponded during the war. My mother came to visit him in Germany when he was a soldier there. He tried to leave Germany, but he couldn’t. So, just after the war he came to Holland and then, a little bit later, married my mother in the early 20s. I guess, 1921. And because he was German and she was Dutch, she became German — that was the Dutch law at the time. I was born in Holland, but because I had a German father, I also became German.

LP: What was your father doing at that time?

HB: He was surviving. Leaving Germany at the end of the war, he tried to survive with the help of my mother and set up some kind of art dealing business with a friend, but that didn’t work very well. He was doing a lot of collage and kept in touch with other German Dadaists. After two years, he started to work as a clerk in a department store. Later, around the time I was born, he opened his own shop called the Fox Leather Company, selling ladies handbags and suitcases on the Kalvestraat. That went fairly well, but soon Hitler came to power and the business went badly and eventually bankrupt. That’s when he decided to become a photographer in 1934.

ERWIN BLUMENFELD Exhibition at the villa Noailles Squash Court. Right: Erwin Blumenfeld OPHELIA 1947

ERWIN BLUMENFELD Exhibition at the villa Noailles Squash Court. Right: Erwin Blumenfeld OPHELIA 1947RENE HABERMACHER: So your father’s first art oriented interest was collage and he was in the Dadaist movement?

HB: He was already interested in photography. He got his first camera when he was about 6 or 7. But his main interest was perhaps the theatre. That was something he was strongly attached to: the German language. His Dutch always remained a little bit feeble to say the least. He worked quite a lot, but with theatre in German language, he couldn’t make much of a living… With his collages he couldn’t make a living with that either but always kept in touch with the Germans — Grosz and Richard Huelsenbeck and other people of the Dadaist movement. Recently there was an exhibition in Berlin on this periods work of my father and a book has been published.

LP: Did he continue to do collage later on when he started doing photography?

HB: No. When he was doing collage, he was also painting — he was a Sunday painter: He did quite a bit of painting on Saturdays and Sundays. But he dropped doing his collage and the painting and started doing photography in Amsterdam. The business went rather poorly, he had health problems and more or less escaped to Paris around the 1st of January 1936. The first year it was very difficult for him to make a living. He got support from the family of his wife, of my mother. On his side he didn’t have much family left. His father had died before the first world war and his mother deceased shortly afterwards. He lost his brother in the war as a soldier in the German army and his sister died of Tuberculosis shortly after.

My father was friends with Walter Feilchenfeldt’s wife Marianne. He was a quite well known art dealer in Zurich. Mariane Feilchenfeldt helped him to rent his studio in Paris at 9 rue Delambre.

RH: So in Paris he got introduced to photography on a professional level?

HB: Already in Holland he was doing it on a professional level. He took many portraits and pictures there, but they didn’t sell much. He got in touch with some French people who came to Holland and they eventually supported him when he went to Paris — like Andre Girard the painter. Then, after about a year later, he started to sell photos to small photo magazines in the US and England, such as Lilliput. In 1937, he met british photographer Cecil Beaton who introduced him to Vogue. My father started to work for Paris Vogue in 1938.

When he was in Paris, he worked only in black and white. Color was not yet really developed for photography. It was very difficult for individuals to use color in their own studios, so he only did black and white while he was in Paris. I should mention that for his Paris period, his publications in Verve were very important. He had some of his striking black and white photos published in the first issues of that magazine. In the dark room, he experimented a lot, but only in black and white.

Then came the war and during the war, we were foreigners in france — we were not really refugees, but were without status, so it was quite difficult. In the beginning of the war, we were more or less exiled, we lived in a hotel in Vessely nine months, a sort of medieval town in Burgundy, France with a really nice cathedral. Then the Germans came and my father and sister were put in a camp. My mother and my brother and I, with the help of some Citroen cousins, managed to escape to the south of France. Our father was then in a rather horrible camp in France. We stayed in the Country until 1941, trying to get out. Then we managed to get a visa for the US — my father had been to the US already, in June of 1939. That was were, I think he took his first color photographs. He came back to France in July 1939 and he was stuck in France for two years. Then when we got to go to the US, he started working first with Harper’s Bazaar for two or three years, switched to Vogue and started doing color photography. At the time, he took his color pictures in the studio, using different color lights and so on — he was very experimental. But for the development and the printing, it was completely out of his hands. It was always done by Kodak. At the time, he couldn’t do anything in color on his own in the laboratory.

Most of these photos here were printed by Kodak. When I say printed, they weren’t really printed, they were large color transparencies. Like big negatives — 12 by 15 inches. I think that all of these photos here were taken in this large format and they were transparencies. The pictures were only printed for Vogue — working from the transparencies. Sometimes my father would give some direction on how they should be printed, but he was not generally involved in the printing itself. Only later, around 1956, they started to develop a new process called C-Prints. He bought the C-Print machine and he could start doing his own color. But C-Prints were very unstable as far as the color went — if they were exposed to light, in a few days they would essentially vanish. So all of his work in C-Print is essentially gone. Even the color transparencies that we have of his work have either faded or changed color a lot. Especially the reds, had faded. So, our doughtier Nadia has worked a lot with Olivier Berg at a laboratory in Lozère to try to restore the original colors. She is using the original publications because those prints have kept their color much better than the transparencies. So what you see in this exhibit is the result of the work that Olivier Berg and Nadia have done.

RH: Would you say that your father was somebody who was very progressive and pushing for new things in general?

HB: I don’t know about new things…. He was for the experimental, which is a little bit different. I don’t know if he was really striving for new things, but he tried to do do things differently and experimented. He was very much inspired by especially old painters like Goya and Renoir and much impressed by Picasso. I don’t know if he ever got to meet Picasso in Paris at the time. But he met quite a few artists as Dali and others.

Erwin Blumenfeld advertising for PALL MALL circa 1957.

Erwin Blumenfeld advertising for PALL MALL circa 1957.RH: But he liked the experimental, so maybe that was something that remained with him from the Dadaist movement?

HB: Yes, that was important to him.

LP: I heard Michel Mallard talking earlier about how remarkable it is that there was no photoshop or digital editing at that time… this image, this one with the lips and the eye, DOE EYE, where the nose is missing and there is color separation, was this done in the retouching process?

HB: This was done in the process of retouching. It was an original black and white picture. It was colored afterwards by my father and by Vogue. They worked on it together. That was a special case because the others that you see were done in color and then reworked. This one did not originally have these colors.

RH: When your father was working, did you often witness his process and how he worked in his studio?

HB: No. When he was in Paris, working in black and white, I was somewhat present. But afterwards, in the States, I was not really present anymore. So I didn’t really witness him working in color.

RH: Was his approach as a photographer more controlled or more spontaneous?

HB: I think both. He was quite controlled — all of these pictures here were taken in a studio. But he also traveled quite a bit in America and in Europe and he took many 35 millimeter color slides. Incidentally, the color of those slides kept much better than the color on the transparencies. But, in the studio, he was very controlled and would take many pictures to get something specific in a sitting.

Left: Erwin Blumenfeld LE DECOLLETE 1952, RIGHT: Henry Blumenfeld in Conversation

Left: Erwin Blumenfeld LE DECOLLETE 1952, RIGHT: Henry Blumenfeld in ConversationLP: In Paris, were you present when he would shoot people in the studio?

HB: Sometimes, but not very often. I was more present when he was working in the dark room.

RH: I recently saw notes from Richard Avedon where he had a black and white print and he marked on it all of the places where he wanted the development to be darker or lighter using manipulation techniques in the dark room. Was your father working with these techniques too?

HB: Yes in the dark room, for black and white, he manipulated a lot. It would have been interesting to see what he would have done with color photography if he had been born fifty years later. At the time, the technology wasn’t there for him to do anything after a picture was taken in color.

RH: Where would your father have his intellectual and creative relationships — in other photography or painting etc?

HB: I would think painting. Very much painting, classical painting. Many of his photos were inspired by different painters. He was also inspired by modern life and by life in NY at the time, in the 40s and 50s. He liked jazz music very much, in the New Orleans style.

And he was quite interested in looking at television when it first came out. We got our first television set around 1950 or so. It was black and white at the time. I don’t think he ever saw color television. Maybe he saw it, but he never had one. He liked movies — but more for the content than for the photography. He liked Nanook of the North, about a Danish explorer. He was interested in movies — liked Erich Von Stroheim and he liked Sunset Boulevard and Billy WIlder.

RH: Was that love for cinema also what led to him making films?

HB: The filming was more in line with advertising. I think he was trying to see if he could use the filming for advertising, rather than to tell a story like in movies. Now you see everything mixed, advertising and movies. But at the time, it was an experiment.

RH: Do you think that your father really divided the things that he did for himself and the things that he was commissioned to do? The time after the war was quite commercial driven in America — was it easy for him to also do what he wanted to do?

HB: For one thing, the black and white and the color were two different things. In black and white, he could do what he wanted. In color, probably none of them were published in the exact way that they had been taken. They were made and developed specifically for Vogue. He did appreciate the possibility to work in color, but the whole fashion business and the way it worked was not very attractive for him. But still, when he had started out in Germany, he had started out working for a textile company and so, even then, he was interested in materials and fashion. Still, he didn’t really appreciate the fashion magazine business, but he knew that he could make his living there. So there were two sides to it for him — on one side, it was a place for him to make a living, on the other side, it gave him the opportunity to work in color, which he might not have had otherwise. He did have certain resentments, which is true for everyone in any job.

Erwin Blumenfeld DECOLLETEE and BLUE both 1952, and POWDER BOX 1944

Erwin Blumenfeld DECOLLETEE and BLUE both 1952, and POWDER BOX 1944RH: There are artists who suffer between the economical need to do something commercial and the desire to make the work that they are passionate about. They can feel torn…

HB: I don’t think that was his case. First of all, he did well financially in the 40s and 50s and he appreciated that. And then, because of that he was able to continue his work in black and white. You might have seen his book “My One Hundred Best Photos”. We have people comment on the fact that there is almost no fashion in that book–he did a little fashion photography in black and white for Vogue before the war, but later he didn’t do any fashion work in black and white. But, it gave him a lot of satisfaction to be able to do that book of his black and white work.

Still…he wasn’t always satisfied with everything. Becoming old for him was very difficult. It made him suffer a lot…some people accept it, but he accepted it quite badly.

LP: You said that he was experimental as a photographer. As a person and as a father, did he also have that type of attitude? And did he transmit that type of approach to his children?

HB: Well….I think he had his ups and downs. He was a very active father in many ways. He was involved with his children and either pleased or displeased with what they were doing. I don’t know….the children turned out very differently. I became an elementary particle physicist. My brother became a writer. He is not exactly politically minded… he is interested in art, sociology in many ways and in the way people behave. He was very rich in ideas my father, perhaps more so than his children.

LP: Did any of his children take an interest in photography?

HB: Interest yes, but not active in photography. Though, my wife became a photographer. She was born in Paris to an Algerian/Russian father and a British aristocratic mother. She survived the war in France — her father was Jewish, her mother was British, but anyway they would have liked to capture her. After the war she came to New York and worked for one year for the New York Times, one of the first women to work in a non-secretary position at the New York Times. Then she went back to France and when she came back to the States, the New York Times fired her because her vacation to France was more vacation than they were willing to give. Then she met the wife of Alex Liberman, the editor of Vogue, and became model editor at Vogue. Her job was to provide models for the photographers. Then she met my father and after a fews years, she started working for him. She started representing him. She never got any lessons from him in photography but she worked with him as an assistant– sending his photographs to different commercial companies. Then after we got married, she became a photographer herself and worked quite actively as a photographer. First a bit in Princeton where we lived. Then in Geneva for a few years. Then we came to Paris and she started working for Vogue and other magazines. She did mostly portraits of personalities and important political people and scientists etc. And other side projects, like children photography too. To a large extent inspired by my father. Of course, after we got married and had children, my father got another assistant, Marina Schinz. She became a photographer too — mostly garden photography and published a book on that.

LP: It is interesting that she worked with your father, who was doing a lot of fashion photography and then she became a garden photographer…

HB: She admired his work very much and when he died, she bought his studio on Central Park South. And she didn’t have a single photograph of his on the wall.

Both she and Kathleen, my wife, probably wouldn’t have become photographers without him. They were inspired by him, but they probably felt that they couldn’t really rival him, so they chose different styles.

LP: Do you think that he was a good teacher?

HB: He wasn’t really a teacher. But he was a big influence. My wife saw how he worked, but he never tried to give her lessons. Same with Marina Schinz.

When my father died, he let Marina handle his photographic inheritance. From the point of view of his will, it was never very clear…He left the photos with her and she tried to handle it the best possible way. So she divided all of the black and white photographs into four lots–one for each of his children and one for herself. Then she gave essentially all of the color transparencies to Nadia. Now Nadia has been quite active in promoting her grandfather’s work. She is now working on an exhibit for next year in Chalands sur Seine. There is a photography museum there and next year they will do an exhibit of my father’s work.

Left: Erwin Blumenfeld BLUE with model Leslie Redgate 1952. Right: Erwin Blumenfeld VARIATIONS, unpublished 1947

Left: Erwin Blumenfeld BLUE with model Leslie Redgate 1952. Right: Erwin Blumenfeld VARIATIONS, unpublished 1947LP: What is the last thing that stimulated you?

HB: What do you mean by stimulated? Something that affected me? Well, the thing that affected me is that my wife, Kathleen, died three months ago. Clearly that affected me. She had been sick, her brain didn’t work anymore. She was going downhill for ten years and in the last two years, she didn’t talk anymore. I don’t know what went on in her head. And three months ago, on the 9th of February, she died next to me…That is the thing that affected me. Also, what affected me was, she died very peacefully next to me. I didn’t realize that she was dead until I felt her and she was still warm and the kin came and said “votre femme est morte”. The morning afterwards, I got the announcement that a second great grandchild had been born. That also affected me. The day afterwards was the funeral and that was quite a moving event–we had five of the grandchildren and they made speeches and my children made speeches and I made a speech. One of the granddaughters filmed it and I now have it on dvd. So, that too affected me. I could tell you more, but maybe that’s enough for the moment.

Kathleen had been very close to my father and she admired him very much. Over the last ten years, she slowly went out of this world.

Thanks to our daughter Nadia, Kathleen had two double page spreads in Match in the last year. Nadia had given the pictures of Kathleen to Roger Viollet and he organized the spread.

RH: What is your work?

HB: I am an elementary particle physicist, experimental! Which is quite different. But I worked first with Cloud Chambers and then with Bubble Chambers and so I surely took more pictures than my father did. Of particles. Millions of pictures.