the museum of everything

Art. What is it ? Where does it start, and where does it end ?

In today’s contemporary art “market”, it seems no one bothers asking the question anymore.

Art, as it would appear, is whatever is made by a self-claimed artist, whatever is recognized by the market.

Enter The Museum of Everything.

Premiering in Paris at the new Saint-Germain location Chalet Society after several exhibits in London, this groundbreaking, sprawling, multi-level and multi-layered show changes the game.

Forget the market.

For founder James Brett, it’s about special things, made by special people, people who haven’t gone to art school or thought of showing their work, much less of selling it.

Antoine Asseraf: What started you on The Museum of Everything project ?

James Brett: I don’t come from a particularly artistic family and my parents never taught me what creativity meant – but as a child I had a lot of it and it always got in the way.

And so I worked in different industries and was working in film, and I remember meeting a very interesting photographer, the late Bob Richardson. He was the father of Terry Richardson. Terry’s a terrible photographer (sorry!) but Bob was a genius. He was the first person who really told me that “You don’t choose it, it chooses you”.

In the same way, I can’t really tell you why I started The Museum of Everything. I didn’t set out to do it, I wasn’t interested in art, exhibitions, nothing. But I was working in film and I know film very well, I studied acting, so I’m creatively interested. And in my travels I started to see artworks, first of all by people in the American South, that was just cool and graphic. I always liked graphic novel and comics as a child – and as an adult frankly – and they started speaking to me.

The artworks were cheap, really like 20-25 bucks, and the more I looked the more I found. I started finding better examples, and realized there was a whole history in America of folk art, African-American art and self-taught art which seemed to come from the individual, it didn’t have the pretension or the words of formally-trained artists, and it was immediate. As a film-maker I loved that, because I’m not really interested in what you are or what you say, I’m interested in the stuff, in what you do.

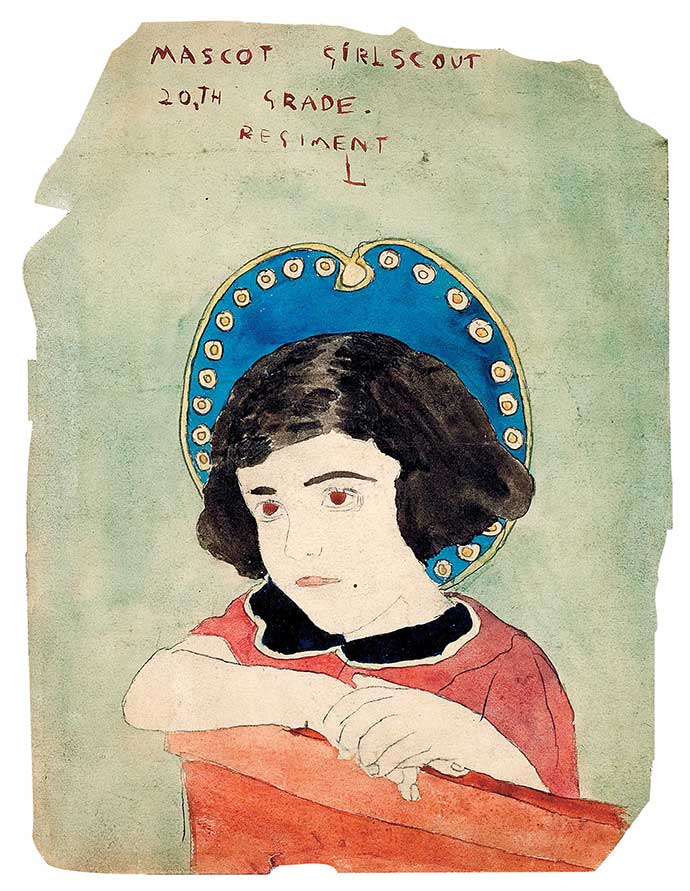

As I continued I saw there were some other areas that had a great psychological depth. For example, the work of Henry Darger. I discovered there was a word for it, Art Brut, of which Dubuffet was the proponent. And that also interested me because in my youth, I was fascinated by the mind, how the mind works, and why we make the choices we do, all of this sort of existential philosophy of life.

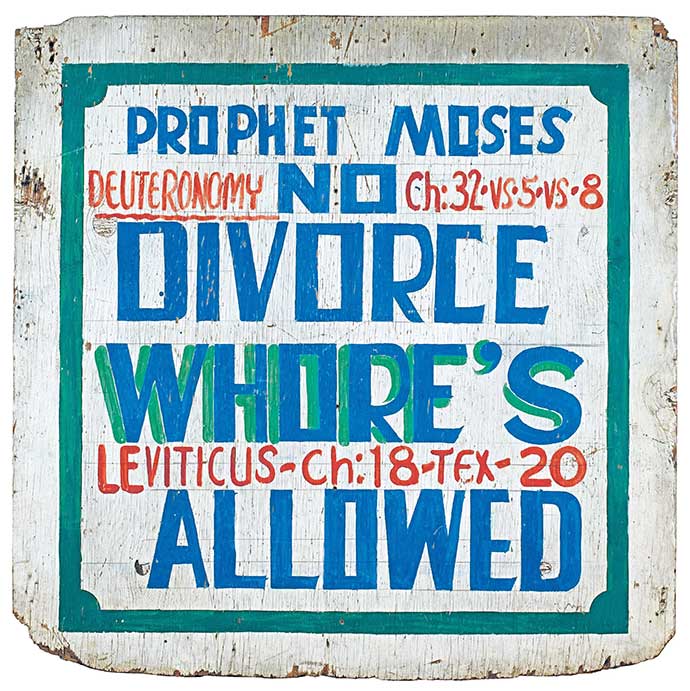

Prophet Royal Robertson untitled (NO DIVORCE WHORE's ALLOWED), c 1980 © The Museum of Everything

Henry Darger untitled (Mascot Girlscout 20th Grade), c 1940/60 © The Museum of Everything

I also saw there were no museums in Britain that really showed this work, and when a big museum did a show, it kind of fell short of the truth and beauty of the work because historical curators often do not present this art with life or communicate the life and passion of these artists. They neutralize it, and contextualize it and dampen it, instead of this great glorious sound, you hear this “eek eek” tiny squeak.

I got to know a few people in the art world, like Hans Ulrich Obrist, director of the Serpentine Gallery, who encouraged me. We then found an old building and put lots of art inside it – and because I had a feeling nobody would come, I contacted lots of contemporary artists who I knew liked this work, people I knew personally, from Mamma Andersson, Ed Ruscha and Maurizio Cattelan, to people like Hans who I knew had an interest….

I said “Would you write about these artists, would you say something to help put this into a context?” – and that became a very interesting contextualization, because it meant I could let others speak for these unknown artists. And because the artists we were showing tend to be more anonymous, less verbal and more immediate and emotional, it was a fantastic mix.

We opened the doors during Frieze in 2009 and we had a monster hit. People wrote about us, we were going to be open for a few weeks and stayed up for 4 months. The show went over to Italy, then we did another one in London with Sir Peter Blake, and the more we did it, the more this thing we created had a life of its own and showed it could do some fascinating things.

WILLIAM HAWKINS, untitled (AtLAS BUI1dINg), 1980 THE MUSEUM OF EVERYTHING, EXHIBITION #1.1, PARIS, CHALET SOCIETY PHOTO: NICOLAS KRIEF © THE MUSEUM OF EVERYTHING

We also did some unusual projects – we did one in Tate Modern where we advertised for self-taught and marginal artists, if they had a vision, if they had a disability, if they were somehow not within the main sphere of art, we said come show us the work, if we like it we’ll hang it up, we’ll do a temporary exhibition – it starts empty and it creates as we build. And people came ! There were so many people at the Tate, it was quite phenomenal! We met people you wouldn’t dream of meeting.

We also did a major show in London in Selfridge’s, which is a department store. They gave us this amazing opportunity, so we decided to use it to say something big – and what we did was go around the world looking for studios and ateliers for artists who have something wrong, what you’d call a learning disability, a handicap, but what other people might say is just a different ability, a different intelligence. It’s a euphemism, but how does the brain work, how do we communicate ?

For these people art was a language, even if they didn’t have a language. And we had every window of the store, so we put their work in the window, presenting them simply as artists. It was a huge show with almost 500 works and we made all kinds of products, because we thought “Fantastic, let’s communicate to the marketplace too”… it was huge hit and in hindsight, a very radical statement.

More recently we just came back from Russia, where we did the same thing we did at Tate. We built a mobile museum, we traveled from Yekaterinburg to Moscow, advertising for artists to see if they would come. That’s a another slightly radical idea – and we’re keen on doing this elsewhere in the world!

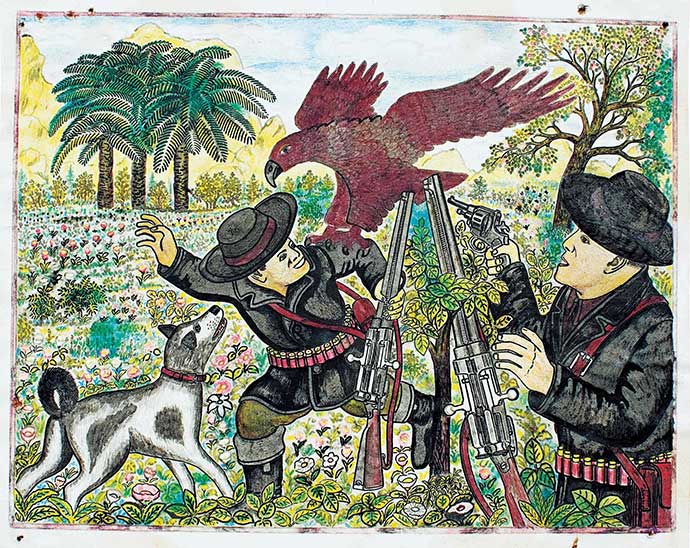

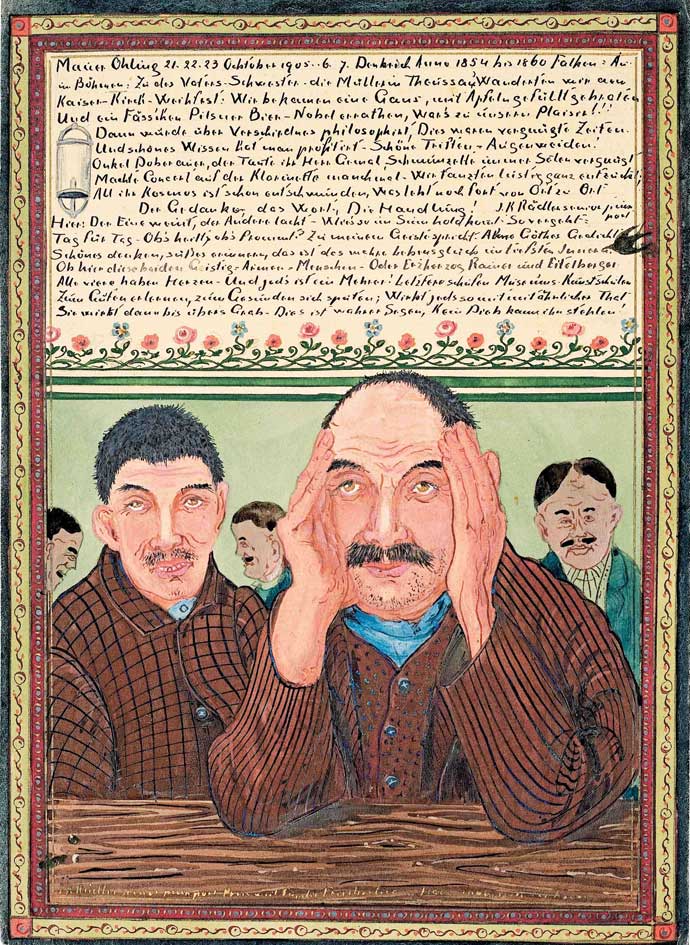

Aleksander Lobanov untitled, c 1970/80 © The Museum of Everything

AA: What is the point where you thought you had a critical mass of art ? How much of this is stuff you collected ?

JB: I was pretty interested, but I’m fundamentally not a collector. Collecting is not interesting. If you ask me who the important collectors are, they’re the ones who actually did something, the great collectors who started the greatest museums of the world. It doesn’t matter if they’ve got 10 euros or 10 million euros. It’s the contextualization.

Absolutely my favorite museum in the world is the Casa do Pontal which is in Rio, started by a Belgian collector, interested in figures created by the local Brazilian artisans, it’s the greatest museum… Sir John Soane and his Soane Museum, unbelievable, filled with objects from around the world – these places are inspiring. They came from a collection, so there is a relationship.

Josef Karl Rädler untitled, 1912 © The Museum of Everything

AA: I was wondering about the process of finding these works – I see a lot of things from Austria, is it because you’ve had the opportunity to go around Austria for while ?

JB: It’s a bit random, truth be told.

There’s often America because America is a big place with a good distribution system, plus there’s the haves and the have-nots so there’s two societies.There’s a lot of cultural values that come into play.

America’s interesting because I realized this work actually had a great similarity to Jazz and the Blues, so much of it was an African American story, and spoke of that particular migration, but it hadn’t been celebrated it in the same way. If you go to the Whitney, they’ll talk about the history of American Art, but you won’t find any of the self-taught African American artists there, they’ll tell you to go to the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Coming back to the question, these artists are everywhere. Not all of them are talented, but they’re everywhere, and for every 10 that are OK, one will be phenomenal. It’s a question of finding them, valuing them, privileging their work, trying to present it in a way that means something.

I come from film, I’m used to mise-en-scène. The thing to do when you make a film is not to keep the script in your head but to be in reality. Actors might be doing it very differently, so you’ve got to adapt, it might not be what you imagined when you wrote it. So when we’re putting on a show, it is equally important to let the building tell you what it wants you to do…

THE MUSEUM OF EVERYTHING, EXHIBITION #1.1, PARIS, CHALET SOCIETY PHOTO: NICOLAS KRIEF © THE MUSEUM OF EVERYTHING

AA: Talking about the building, how do you find a space like this ? Looking for a specific neighborhood ?

JB: No no, it’s a chance situation. Our first show in London had been in a similar building that we played around with. Of course I wanted to come to Paris, I was really interested. Marc-Olivier [Wahler, former director of Palais de Tokyo and founder of Chalet Society] had visited the museum. We had a chance encounter in Marrakech [Biennale] where we sat down and he told me what he was doing. He said “I’m creating this new sort of art space, do you want to come see it ?”.

Chalet Society, which is his space, was a temporary space here in Paris, so we came here, I looked around, and it seemed a fantastic fit. So there was no looking – in the life of the museum chance encounters are the way it tends to work – it was Marc-Olivier Wahler’s relationship with the building, they lent it for the project, that’s how it came to be. I couldn’t ask for anything more. He’s my host, I’m the lodger. And when I’m gone there’ll be another better looking lodger…

MORTON BARTLETT, untitled, c 1950/60 THE MUSEUM OF EVERYTHING, EXHIBITION #1.1, PARIS, CHALET SOCIETY PHOTO: NICOLAS KRIEF © THE MUSEUM OF EVERYTHING

AA: What changes did you make if any, how did you curate the content for Paris, some things that would speak more to the people in Paris ? I guess at this point you’ve already had several exhibitions and you have a larger amount of art. Or did you just see with the space ?

JB: Less French things. And more French things. For example here there’s a strong history, an intellectual appraisal of self-taught and outsider art and Art Brut. There are other great spaces here in Paris, a great collection at ABCD, Antoine Galbert’s Maison Rouge, they’re all interested in this kind of material… They’re fantastic places but they tend to speak in a more narrow form. I thought it was important not to double on what they already did, not to present artists they’ve already shown, because we wanted to get past the idea of Art Brut, because it’s a limited idea, if you rely on that you don’t go anywhere.

Both Marc Olivier and I are interested in much bigger ideas, philosophical ideas about art and creativity as “what does it mean ?”. I believe you can answer this question with the artist who makes something for himself or herself, without thinking of the terminology and the words. It gives form to enormous ideas which have not been brought into common art culture. In my opinion, they’re hidden inside Art Brut but they’re much bigger than Art Brut.

William Scott untitled, 2009 © The Museum of Everything

The best example is an artist with a learning disability who can make phenomenal work without any cultural knowledge or context. It’s a language. And the only word you can give to it is art. I guess that’s what’s important to do, and the artists were chosen with these philosophical ideas in mind.

It’s very subjective, but at the same time we worked with the building, trying to find the right alleyways, pathways, spaces.

It’s a dialog, but I thought about what has been, and what could be, and what’s fascinating now that the show is open is that we’ve had so many major artists here, thinkers, talkers … and they all say yes, they all see what we’re trying to say.

Because I come from film I always try to create a narrative. People change as they walk through the show, from the moment they walk in at the top of the stairs and then as they make their way down. They become different human beings and that’s very interesting to me.

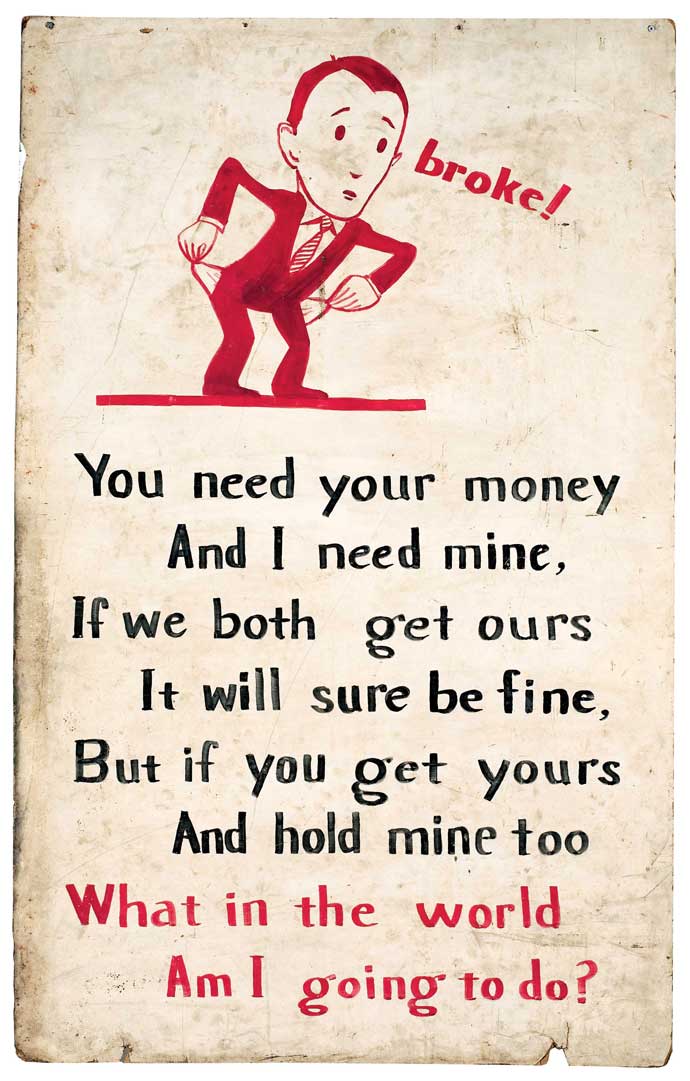

George Thaxton Miller untitled (broke!), 1965 © The Museum of Everything

AA: Your exhibit made me think of the book “Beautiful Loser” about the art which derived from skater culture, made mostly by people who also lack artist training…

JB: As our project evolves, my thoughts evolve on the process: the thing about Russia, we met 100 artists a day, some not of interest, some of incredible interest – and so many of them had so much to say.

Some would put a matchstick down and talk for 20 minutes… the smaller the piece the longer the talk! Everybody’s busy expressing themselves, we live in a culture where that’s encouraged, but mere expression is not enough, I mean have you ever sat through those movies and 2 minutes into the movie you want to kill yourself, 10 minutes into it you’re pulling your fingernails and your eyelashes off, and 20 minutes into the movie you’re writing shopping lists for the next 2 years of your life?

It’s a travesty of modern times, that expression is important. Well it is and it isn’t. You don’t have to force people to engage with your ramblings on life unless of course you’re fascinating, unless of course you’re that special person who has that gift, and we all wanna know, and we all wanna see it and love it.

THE MUSEUM OF EVERYTHING, EXHIBITION #1.1, PARIS, CHALET SOCIETY PHOTO: NICOLAS KRIEF © THE MUSEUM OF EVERYTHING

AA: I guess that’s the limitation of film, you’re forcing people to look at it in this framework with this time, whereas a museum if you don’t like it you just walk faster and get out of it.

JB: You are so correct. I love the lack of the sensation of time in a museum. You can walk through this museum in 5 minutes or less. You can take 5 hours. You choose the amount of time you choose to engage with any work. It’s completely in your hands, the opportunity to stay is there for you and that’s a phenomenal advantage.

I don’t believe there are any bad movies in this show, but if there are, you can just walk past them. I think my point though is about expression. Everybody has something to say. Our job at The Museum of Everything is to find those creative voices, the ones that are truthful, that are hidden, whatever hidden means, or ones which somehow connect to this bigger idea of “Why do we exist ? Why does creativity exist ? What does it mean ?”

For me, I keep going back to the artist with the learning disability. I’ve met many now, and some you really want to communicate and connect with them and it’s very difficult. But you can do it through their work, you can see it, you can feel it no matter how abstract, you can feel the energy and the way their minds work and their bodies. And to me that’s the most beautiful part of it.

It’s not the same as a child, because someone with a disability is not a child, they’re adults, but they’ve developed in a different way, their intelligence is unusual.

Today we realize that in the diversity of the human experience in the 21st century, education and language can be barriers, as much as they’re enablers. One of my favorite writers, William Burroughs, says: “Language is a virus from outer space”.

I love words, I use them all the time, but sometimes it’s better to shut up.

Museum of Everything founder and director James Brett, by Antoine Asseraf.

AA: What are some of the upcoming projects after Paris ?

JB: We’re going to go back to Russia, because we traveled through the country, but when we arrived in Moscow the place wasn’t built yet, so we’ll go back to put on the show, which hopefully will then travel…

And anyone reading this on the blog is free to invite the museum somewhere – half the time we use the museum as an excuse to visit places we haven’t been to! I love the idea of the museum becoming an international force in the promotion of creativity as a human right. We’re wide open!

AA: I think what’s interesting is that you don’t question whether this is “craft” or whether this is a tradition which is being repeated…

JB: Sometimes you meet artisans, but what’s interesting is when they change. Michael Gerdsmann is a registered blind artist from Germany. He was taught knitting to do covers for teapots and was selling them in the market, and thought “What’s the point of this? I need to do something better!”. So he started making covers for iPods and headphones, electrical equipment, and had this idea that somehow these two were well-matched. So he started as an artisan and became an artist.

AA: Today we think “this is an artist, this is his expression, and we value his expression” because it’s the Artist. In other countries there is still traditions, and who makes the one particular object doesn’t seem important in that context, it’s more about the history of the object…

JB: There is a difference between the person who makes for himself and the person who makes for the market. I wouldn’t talk about artisans, I would talk about who the work is being made for. Trouble is, according to that theory, Jeff Koons is an artisan and Damien Hirst is an artisan… and by the way, I think they are, they’re very good artisans!

[My mother arrives and the conversation turns to cheesecakes].

The Museum of Everything – Exhibition #1.1

at Chalet Society

14 Boulevard Raspail 75007 Paris

Until Christmas 2012

Until February 24, 2013.

Miss Marion Hopscotch performance

Saturday November 10th from 3pm-6pm

1 Comment

-

After visit to Prinzhorn Collection (Heidelberg, 2005), Ghuslain (Gent) and some other places in years since, Art from people not trained – as seen at Museum of Everything, is becoming familiar. This traveling exhibit, seen by me in De Kunsthal, Rotterdam in May 2016, has a direct appeal and is an inspiration when ‘creating my views of places in society’ by means of assemblage.

For diehards: MLB galery Amsterdam, June 2016

regards, Drager